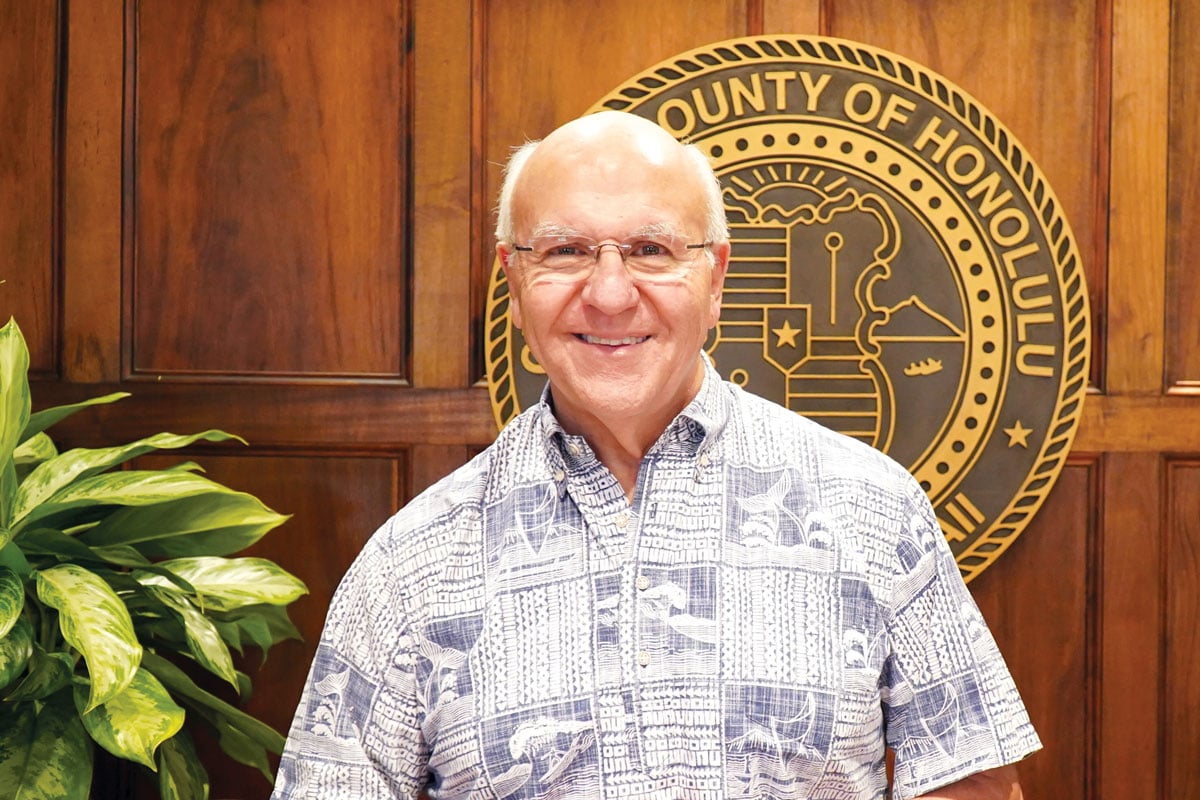

Mayor Rick Blangiardi’s Playbook

Mayor Rick Blangiardi discusses his second-term strategy to tackle our city’s most critical issues.

Honolulu voters this summer gave Mayor Rick Blangiardi a resounding primary election victory, earning him a large enough margin of votes to skip this month’s general election. As the former television executive and football coach heads into his second term, we sat down with him at Honolulu Hale to learn of his priorities for the next four years on such urgent topics as crime, homelessness and rail transit.

(Answers have been edited for space and clarity.)

Gun violence and random attacks have folks on O‘ahu worried about spiking crime. How are you responding?

We’re doing everything we possibly can to build up the Police Department because public safety is the overarching No. 1 priority. We first came into office, I signed a three-year police pay contract [with] 5% raises each year, compounded to about 22%. We agreed to three 13-hour shifts a week for police. We try to help with the recruiting. We have an incentive bonus, $25,000 for signing.

What’s being done in Chinatown/Downtown, where crime hinders revitalization?

By the end of the year, we’ll have 60 cameras in Chinatown. We came into office, there were 26 cameras. Only one worked. It was 1990s technology. Now, we’ll have 60 cameras, each of which has five heads, which totally records everything. They can zoom in on anything. In fact, they have audio, too, so if somebody screams, the Police Department can help. This is state of the art.

When you became mayor, you took over the most expensive public works project in O‘ahu history, with a price tag now topping $9.8 billion. We know the rail has been plagued by rising costs, delays and funding issues. A 10.75-mile segment opened in June 2023, but to get the federal funding, you compromised on a shorter route, ending in Kaka‘ako instead of Ala Moana Center. By the time you complete your second term, how far will rail reach?

We’ll be Downtown. We’re coming down the Dillingham corridor with the utility relocation. We already have the guideway built to Middle Street. We’re working on the stations, and we’ve now begun to run [after-hours test] trains from Aloha Stadium to Middle Street.

The Skyline now runs from East Kapolei to Hālawa. What will that mean when it reaches local job centers at Pearl Harbor and the airport, projected by the end of 2025?

We think the ridership, once we get past the two [Pearl Harbor] gates and the airport, could probably reach 20,000 to 25,000 a day. The belief is that’s the incentive to get a shift in ridership because now people can take it to work. At that point, 84% of the system will be built and operating.

The latest survey estimates about 5,000 houseless individuals on O‘ahu, half on the streets and half in shelters, and the Institute for Human Services’ executive director, Connie Mitchell, tells you that’s heading closer to 7,500. Why the increase and what is the city doing?

Homelessness is a very complicated problem. That still represents less than 1% of our population. It’s a source of a lot of aggravation, a lot of frustration for people.

You’ve partnered with the state on a respite center, bought transitional housing and are expanding the Crisis Outreach Response and Engagement, or CORE, team approach. What’s next?

I want to be aggressive with this, but as humane as possible. With CORE, we’ll have four ambulances, the [refurbished city] bus, six SUVs, a CORE staff of 30. We’re looking for another 10 staff, possibly more. For mobile crisis, they go out, they build trust. They respond to calls if they see somebody lying on the street. Typically, in an emergency room, what they used to give them before was a $1,000 shower, maybe treat some open wounds, feed them and put them back out. We’re not doing that. We have wraparound services: We’re under contract now with IHS, Catholic Charities, the North Shore Medical Group, Lutheran Health Services, Premier Medical Group. The idea is to get as many as possible into permanent supportive housing.

How are you responding to reports of people flying here without housing, jobs, support?

We learned yesterday from Connie Mitchell that 80%—12 out of every 15 people—that they’re taking into their shelters now are from the mainland. I am livid. We’re going to do something about that. That’s where the growth has come from. We’ve done a lot of work at trying to deal with our local people, but I’m going to fight that number with everything we can, even to the point of doing what they pretty much did during COVID, which is intercept them. If they have a one-way ticket, you can’t come in here unless you’ve got housing, an address and everything else. We’re going to turn them around, detain them and fly them right back. That would be my goal, and I think legally, we can get that done. This is our own border crisis. They’ll overtake our system. Our resources are finite; they’re strong and they’re good, but finite.

You face a longtime crisis at the Department of Planning and Permitting: bureaucracy that delayed permits for years, outdated technology and indictments for fraud related to taking bribes for expedited permits. What’s changed?

We were in office for only four months, and the feds came in, in April, and arrested six people, and the first person that went to jail was a 72-year-old grandmother. We had beyond management dysfunction, systems dysfunction, and had that to deal with. We took it upon ourselves to invest in people, technology and processes. In one year’s time, your permits will be two to four weeks, we’re going to hold to that.

What’s the city doing for affordable housing?

We came to office, there was one person in the housing department, and they were deferring everything. We weren’t working with developers. Even the affordable housing fund, all this money had lapsed. It’s a crisis for decades, and the state was the only player, yet the city had a very big responsibility and opportunity to help with that. We’ve now got a full-blown housing department. We have a strategy. By the time we leave office, we will have created 18,000 units. About 56% will be for ownership, and 44% will be for rental across all demographics.

What’s the worst thing about being mayor?

It’s the frustration of the time that it takes to get stuff done. This job is about problem solving, but to solve a problem, you really have to understand the problem. That takes time because with these problems, nothing is linear, everything is complicated, and there are laws and ordinances and practices. And even sometimes on a deep dive, you don’t even know why they’re doing what they’re doing. Once you understand the problem, you have to develop a solution, and then that solution is going to go through procurement.

What’s the best thing about being Honolulu’s mayor?

This job for me is the challenge, responsibility and privilege of a lifetime. To have work that matters like that is the best thing. This team is getting things done—good things—and tackling the tough problems. I understand my role as mayor. I understand what the responsibility is, but this is definitely a team sport.